The Chimney Portal

Supernatural agents and cosmic coziness on Christmas eve

This is the story we don’t tell ourselves about Christmas eve, the night when we purposely invite supernatural agents into our homes. Maybe it doesn’t seem so weird from a modern perspective, because Santa is so dang nice. He brings presents and eats the cookies we leave for him. This is the magic of Christmas, we say.

But the historical context of these same spiritual behaviors (and I mean spiritual in the old way, as in, concerning spirits) is instructive, and illuminates the darker emotions around the holiday that can be vexing for children and adults alike.

Let’s start here: most of holiday decorating is done in the service of spiritual protection. These traditions are not centered around celebrating the divine child, the supposed reason for the season, but repelling harmful spirits. Wreaths of pine and spruce are evergreen amulets that protect doorways from bringing in disease and death. Garlands tied with red cloth have been used to ward off evil spirits for centuries. And like the woods people of Northern Europe have been doing since the time of Odin, we leave an offering of food at the table.

These are all ancient apotropaic agents, that is, objects and rituals used in liminal spaces to combat the uncertain terrors of the night.

Apotropia and the archaeology of belief

For centuries in Europe and the British Isles, magical objects have been placed in the threshold spaces of homes: above lintels in door frames, under windowsills, and concealed inside chimneys and smoke holes. Common examples include horseshoes, children’s shoes, sacred words, and iron crosses. Sometimes these objects are hidden; other times they remain in plain sight.[1]

The material study of apotropia is known as the archaeology of belief, and despite the immense variation around the word, these ritual practices are quite common because there’s only so many ways that the human visionary experience can get mapped onto the calendar, the landscape and the architecture we create to focus natural forces already in play.[2]

All over the world, thresholds, those spaces between places, are magical. Paradoxically, openings into the home provide the ability to move freely and welcome guests, heat our dwellings, and let in the fresh air. At the same time, they open the home to unwanted guests, foul smells and harsh elements. Fear resides here in the space in between, and also a secret dimension. Supernatural forces arrive and congregate here in these spaces between, existing in what archaeologist and folklorist C. Riley Auge calls a “temporal and spatial sector separate from mundane reality.”[3]

This is why liminality feels dangerous: in the ambiguity lies a deeper cosmic ambivalence, an attitude where the line between the worlds, between the living and the dead, is erased. And that’s why liminal zones are precisely where magical objects provide the most comfort.

Isn’t that pretty much the deal with coziness and the winter vibe in general? It’s an apotropaic effect where we indulge in the contrast of being warm, safe and secure against a backdrop of the cold and unprotected. Coziness itself dabbles in cosmic horror, with warm tea and cookies in hand.

Mythic geography in liminal times

Earlier, I brought up the example of wreaths used to secure the home, and we see in another example the tradition of hanging mistletoe. In this case, the mistletoe brings tidings of health and even intimacy. Viscum album and all its varietals are poisonous but have a long history of use in ancient medicine. Pliny the Elder recorded how the Druids of Gaul considered mistletoe a sacred plant that had powers of fertility. Not any mistletoe was considered powerful by the Druids however; it was picked only from oak stands, part of the sacred landscape, or what historian Ton Derks calls a mythic geography. [4]

So if you’ve ever felt some strong cognitive dissonance on Christmas eve, this may be why. Children pick up on it pretty easily, too: they are simultaneously fascinated by and not-so-secretly terrified of Christmas Eve. And why not? The normal routine of sleep and waking and the emotions surrounding them is completely upended. Sleep comes late and is marked by multiple panicked awakenings at the normal sounds of the night. Was that the patter of reindeer feet? The ringing of bells? The sacred landscape—the unmapped, the spirit territories beyond the hearth— is loud and buzzing with activity. Again, the coziness effect is here, in a crystallized form we could call cosmic coziness, a full bloom of dopaminergic activity that quickens the pulse and deepens the satisfaction of the hearth.

To review: on Christmas eve, we leave the chimney clear for penetration by spiritual entities. By guarding all of the other openings of the house with amulets of protection, we effectively funnel all of the energetic vulnerability of the dark night into this sooty opening and invite a specific demi-god we call Santa Claus into our homes to induce cosmic coziness in sync with the darkest nights of the year.

Why spiritual protection?

It’s not just the pursuit of coziness though, and Santa isn’t always nice. The need for spiritual protection makes more sense when we look at the origins of these holiday traditions that still hover on the periphery of our awareness. St Nicholas, the Christian saint from Greece who loved giving gifts to children has been grafted onto the Yuletide celebrations that were held in honor of Odin the Wanderer, a shape-shifting, many-named god of the North who led the Great Hunt and rode an eight-legged horse. Of particular relevance here is the fact that Odin rewarded children who left food for his horse by filling their stockings with gifts.[5] He delivered them, of course, by going down the chimney, a favorite entrance of witches and shamanic figures the world over.

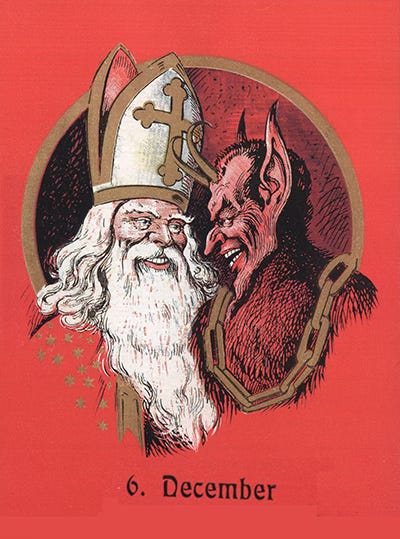

But Odin isn’t the only smoky spirit that entered the home in pre-Christian Europe. Thanks to the Hollywood horror scene of the last decade, you probably know about the Krampus myths that come out of the Germanic traditions. Krampus: the anti-Santa, the devil in the details, the moral enforcer for all those little children who were not quite good enough.

Another mythic strand can be seen in Perchta, the 16th century Germanic mountain goddess, who, like Krampus, had one good foot and one enlarged foot, often called a swan foot, indicating a penchant for animal transformation. If no one left an offering for her on her feast day, Perchta was known to slit people’s bellies open, pull out their entrails, and stuff them with straw. She came into the home around the mid-winter solstice, and also around the twelfth night, or January 6th, and delivered gifts to hard-working children but a death warrant to slackers.[6]

Unlike the beatific St Nicholas, Perchta didn’t need a dark consort because she contained the dual nature of judgment within herself: she could show up as a lovely white-robed woman or as an old hag, depending on the moral purity of the household. I guess you could say Perchta is a nondual Santa, transcending awe and horror.

In my neck of the woods, eastern Pennsylvania, the Germanic traditions hold a lot of sway in contemporary practice. American Christmas traditions come mostly through the Pennsylvania Dutch, those German-American settlers who arrived in large numbers in the Eastern woodlands during the 18th and 19th centuries.[7]My children don’t explicitly “believe” in Santa Claus anymore but we still practice the rituals as the solstice approaches and the veil gets thin.

Yes, this week ahead, I will put up the wreaths, the garlands and the mistletoe.

Just like Dickens suggests, I will be on the watch for big dreams that are roused from that unspecified dread and over-vigilance (and the poor sleep that follows). And damn straight I leave out cookies and milk for the spirits.

Portions of this essay were previously published on Matt Cardin’s Teeming Brain, and still more is adapted from my soon-to-be-rereleased book Lucid Talisman: The forgotten lore of dream amulets.

[1] Hoggard, B. (2019). Magical house protection: The archaeology of counter-witchcraft. Berghahn.

[2] Augé, C.R. (2022). Field manual for the archaeology of ritual, religion, and magic. Berghanhn.

[3] Augé, C.R. (2007). Supernatural sentinels: Managing threshold fears via apotropaic agents. Presented as the annual meeting for the Society for the Anthropology of Consciousness, San Diego, April 1-3rd.

[4] Derks, T. (2010). Gods, temples and ritual practices: the transformation of religious ideas and values in Roman Gaul. University of Amsterdam Press.

[5] Siefker, P. (2006). Santa Claus, Last of the Wild Men: The Origins and Evolution of Saint Nicholas, Spanning 50,000 Years, New York: McFarland & Co., 2006, 171–173

[6] Grimm, J. (1835). Deutsche Mythologie (1835). From English released version Grimm’s Teutonic Mythology (1888).

[7] Igou, B. (1998). “Pennsylania German Christmas Traditions,” Amish Country News, Winter 1998.

This entire piece is incredible. I'm a spirit worker, but I never really thought about the why behind the holidays causing an uneasiness within me. Once I left Catholicism, I only thought of Christmas as a night to be with my family. I didn't even think of the spirits people are unknowingly welcoming into their homes, even though I work with spirits daily. 😆 Aside from that though, I must show appreciation for the Krampus/Jack Nicholson. That's hysterical 🤌🏻

Most of that information I've Heard of except for Odin.. that's awesome